69 - Can Baltimore’s Art Help You Navigate Crooked Paths? | Ernest Shaw

Download MP3Rob Lee: Welcome to the Truth in This Art your source of conversations connecting arts, culture, and community. These are stories that matter, and I am your host, Rob Lee. Today, I am thrilled to welcome back my next guest, who first joined me on the podcast back in 2022.

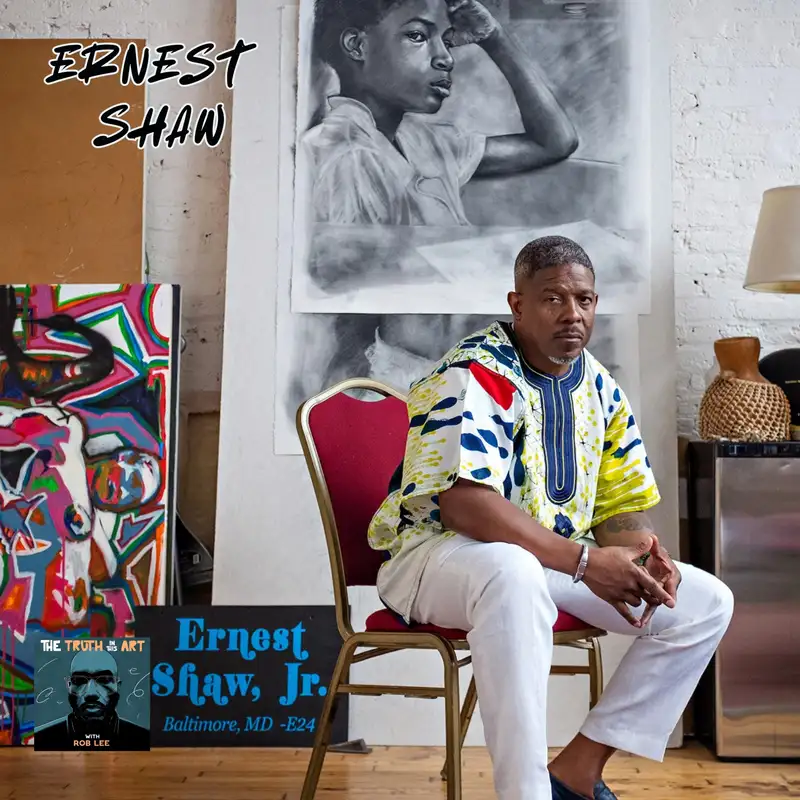

He is a muralist, painter, and educator, born and raised in West Baltimore, and is deeply connected to the city. So please welcome back to the program, Ernest Shaw. Welcome back to the podcast. Thanks for having me.

Thanks for that. Thank you for making the time and coming back on. It's especially with this sort of season of the podcast. It's really been about prioritizing and having folks on again where it's just like, hey, I think there's more conversation to be had, or hey, you know you didn't do a good job at that interview, you could do more, or like, all right, this person's been doing some interesting work.

So in that instance, I went through and I was just like, all right, let's see if I can find 50 to 60 people coming up on 900 interviews, right? So I'm like, yeah, yeah, there's people who had had no idea, like, really? And I started looking at like, who have I talked to over the six years that this podcast has been around? So I've had some folks from 2019, some folks from 2022, which is that big marathon year where I did over 300 interviews in that year. And you were one of the people in 2022 that I wanted to have come back on and I'm glad you accepted. So, you know, it's been three years. And if you will, could you reintroduce yourself to the listeners who might not know who you are, you know, you're a legend, but you know, people, people have these weird memories. You have these weird memories. And in that, could you tell us what you've been working on recently?

Ernest Shaw: Okay, well, my name is Ernest Shaw, born and raised West Baltimore to be specific. Artist, educator, father, now grandfather. Congratulations Yeah, thank you. I appreciate that. It's a big transition. You know, recently retired from Baltimore City Public Schools. I still teach adjuncts at Maryland Institute College of Art and Johns Hopkins.

Rob Lee: So it's very interesting time indefinitely throughout this conversation. It'll fill in more of these sort of details about you. And I love the, you know, the specific of West Baltimore because I am too originally from West Baltimore. So it's a really interesting time where we're doing this.

It's about mid-September of 2025. Just kind of set the stage. What's in your mind currently? What's in your mind these days? Art related or just in general? Sometimes artists life and life is art. Okay, cool.

Ernest Shaw: Good answer. Good response. Well, what's on my mind? It's somewhat related to what's tied to the fact that I am a grandfather now because now I'm thinking about the world, not simply or my purpose in the world, not simply to make a better place for my daughter and or my daughter's generation, but now for my granddaughter's generation. You know, what things can I do? What things can I put in place? What things can, how can I contribute to a world locally, regionally, nationally, internationally in a way that's going to make a positive contribution to make this world a better place for my grand baby, for my granddaughter and her generation as well. It sort of kind of opens you up to thinking about life in a different way. And I'm blessed to still have both my parents. So I'm watching my parents age gracefully. And at the same time, I have this, this grand baby coming in, you know, it just really, it requires that one focus, you know, requires that one focus and spend time in meditation, spend time contemplating and really getting locked in, you know, you'll find in your groove, you know, vibrate in a way that has you in tune with, without getting too, you know, too far, too esoteric, but you know, find your groove, get locked in in a way where you, you're vibrating on a frequency that, that allows you to make a positive contribution.

Rob Lee: That makes sense. And I'll add this extra piece to it. Like I don't have any kids of my own, but you know, I'm in this sort of stepfather space and I have a stepgrandchild, I'm 40. I'm only 40, but I've got stepgrandson now.

He's, he's probably eight months old. And I didn't think it would be a thing, but it's like, all right, what can I pass on to make this here? And I have a niece who's like a year old. I'm like, ah, man, now I have to be responsible and start thinking of things. And not that I'm irresponsible, but it's an extra layer of, as you said, that that's sort of locking in and thinking about it.

I'm thinking, you know, from my small space of what can I contribute? What can I pass along through my action and being able to do some of the things that I do? And then also, as you, you touched on as well, having both of my parents and learning from them and learning their stuff is like, you know, the, what is it, the grio? There's so like, how do you pass some of these stories along? And how do you pass some of these things that as we're experiencing life now as adults, we're seeing certain things get wiped away and we have to be in some ways people who are carrying that on. I think having that added responsibility or feeling an added responsibility of continuing to do this, you know, and try to take it in a much more serious way versus you can have fun with it. But also, you know, I see that there's value in it, encouraging it to that sort of next gen. Absolutely.

Yep. So, you know, we touch on the Baltimore thing. I'm a Baltimore, you're a Baltimore, we're all Baltimore. So how, how, how does it shape you? Like as we dive back on that, I think, you know, as a person who's a thinker, you're a thinker, I get his rebrose. You know, some people like, yeah, here's my answer, here's my take. Like you didn't even think about it. It's just, wow. And so, you know, perhaps revisiting this, but how is Baltimore shaped who you are as an artist?

Ernest Shaw: Great question. You know, Baltimore's an interesting city, interesting city, historically and culturally. And as I've grown, once I became an educator, I began to learn more about Baltimore, especially through books like Not My Neighborhood or Black Butterfly. Like those, those books really give you context on historical and cultural makeup of Baltimore. So, you know, Baltimore shaped me in this way. Traditionally a blue collar town, right?

At some point, my brother and I were third generation Bethlehem Steel employees. Right? Yeah. Raised off of Bethlehem Steel. You know, that type of blue collar, you know, dad working swing shift, 40 plus hours a week, sometimes going to work on Christmas Day, you know, but making sure the lights always stayed on, you know, did not grow up financially wealthy.

Sure. Having said that, I grew up culturally wealthy. And Baltimore plays a huge role in that. As I stated previously, was Baltimore originally up in the upton neighborhood division street, one, two blocks away from quite seeing food, where quite seeing food may grew up, where Thurgood Marshall grew up.

You know what I mean? One block over from Pennsylvania Avenue. There's a lot of culture associated with those, with that neighborhood specifically. So, you know, Baltimore is an interesting town. I consider it the northern most southern town. Even though growing up, we were taught that it was the southern most northern town. There's a slight nuance there.

Oh, it has its northern facade at times, but it's a southern city. You know, so you taking all of that into consideration. It's a very real, people used to work gritty all the time.

Or vibrant. Yes. Yes. Very, very transparent. You get what you, you know, there's not a lot of surface level. There's really no facade to Baltimore. Baltimore is what it projects itself with, you know, which is not just the wire. It's almost in every interview that I see someone from Baltimore being asked about Baltimore, they give that disclaimer. It's not just the wire, you know, but, you know, but yeah, as an American, let me recognize that term as a city in the United States, as a truly original city, United States being the major city of Maryland, which was the only Catholic colony of the original 13 colonies, Baltimore. A very important role from a civil rights standpoint from a, you know, lay in the blueprint for the development of other cities all across this nation. You know, so, you know, Baltimore has shaped me culturally, shaped me intellectually. As a bi-proud like a Baltimore City Schools. Yeah, you know, I think saying that I love this city is another statement. I respect the city just as much as I love it, you know, which is why I still call it my home. That's great.

Rob Lee: It's well said. And yeah, I think I agree with all of that, you know, like being from here, obviously, and it's not a lot of pretense that is here. It's like, you kind of, you know, get what it is.

You're here. And, you know, from my vantage point and from being able to talk to so many people, I'm always curious as to, you know, how people see it and in which ways they see it. Because there's so many different ways one can see it. You know, someone is like overly negative about it or only seeing it from that vantage point and that kind of shapes how I think a conversation could go. Maybe what their perspective is, I think when someone is more neutral or even more like, well, I'm still here, you know, I love this place. I respect this place.

And, you know, I have that. And I see sort of in some ways an insurgent sort of vibe of, well, we need to rebrand and reshape Baltimore into the image of something else. And it just ranks kind of phony for lack of a better term. So sort of hearing that piece of like, you know, it is kind of what it is and seeing like in those instances where something that is a reimagining of a place, it's almost a message that what it is isn't good enough.

So let's reshape it. And I see that those things often don't stick because there's no foundation behind it or no foundation under it. And that's kind of, and that's one of the things that I see in doing this, you know, like I don't try to over leverage or over index on, yeah, we're still real here. The authenticity, like I try to have a real conversation. I try to value the real conversation. And if I connect with someone in a really deep level, great. If I connect with someone on more surface level, but I present what I present pretty generally, and I see more and more folks trying to capture that idea. And I see the elements of my stuff popping up in other people's work. And I'm like, that's great.

I'm influential if I'm being diplomatic about it or people are feeling people jacking myself. So it is one of those things where I guess to land a ship here on this piece. We seek and we value that authentic feeling, that thing that just feels real. And I think that that's baked in here. And when something isn't quite that, it's grasping for that realness.

Ernest Shaw: Yeah, you know, I've seen aspects of my work in other people's work. And I think, you know, imitation is the highest form of flattery. I think is that is that the proper term? I think that's one of the things. One of the ways of looking at it. Because I share my work, you know, so when we share it, it no longer really becomes it's no longer our work. Yeah. Once we put it out there, you know. But I feel you.

Rob Lee: Yeah. Yeah, I feel you. So going talking about your work of this, we kind of move it to this part. I see themes of community perseverance and you saying it's that it's out there. It's, you know, it's being shared and ancestral lineage, millennia run through your art, run through your work. You know, and you've touched on it a bit as far as the familial like changes and being a grandfather now and sort of thinking, you know, deeper for that next generation and being in this sort of presence. Now, why are those things so much important now in 2025 moving into sort of 2026?

Ernest Shaw: You know, without getting into too much trouble, it's clear. It's clear that as a. I'm going to use the term nation. The United States is in transition, but it's in transition just like.

Any other former empire. You know what I mean? Yeah.

What's interesting though, and this is one of the things that keep me going. Is that let's use the British Empire, for example, the British Empire. When the British Empire finally fell. It did not cease to exist.

London's still there. You know, that there's still influence in other parts of the world. You know, you know, it's there's a way in which we're conditioned to think that. You know, without capitalism or, you know, without being the greatest country on Earth and air quotes that we will cease to exist. Or if and when the United States falls, the world will cease to exist.

The universe will cease to exist. That's kind of been baked into our that's kind of been baked into our consciousness. Sure. You know. That's not how I see things. You know, everything has a beginning and an end. If we are to. Thrive, survive and thrive beyond what is known as the West. Sure.

I'll do it that way. It belongs beyond what is known as the West. Then we have to begin to create that future now.

You know, throughout work. So I'm not overly pessimistic about anything. I think it was James Baldwin that says he refuses to be a pessimist.

There's no way he can be a pessimist. Because you cease to live, you know, and I'm paraphrasing. So it's hard. It's hard sometimes. It's difficult to navigate some of what's going on currently in the world. But there has to be a simple as, and I'm not going to use the word hope or faith, but there has to be a simple as a perseverance and imagination. What do you imagine the future to be?

And how are you going to contribute to that? Right. If you want to be hopeful, you can. Let me be clear that I just choose to focus on imagining the future and my community's place in that future. And I try to work toward assisting and creating that.

Rob Lee: So with that, and I think it's really well said and definitely thought out, you know, where you're taking time to think about how to persevere, how to combat some of the things that I hear while recognizing that it's, you know, when people say there is a chapter ending, you know, it's sort of bad.

And I think when a chapter or cycle or stage sort of ends or the concept of what it was like, you know, yesterday is over, tomorrow is yet to come. So, so that there's always challenges and opportunities, I think for folks who are artists, folks who are in the sort of creative and arts and culture sort of space, I'm somewhere in a journalism that we're covering arts and culture. What are the opportunities that you see out there?

What are the challenges, obviously, that you see out there for, for artists of any stage in their career? Cause when you think of AI, when you think of all of these different things that are there, you think of even from the podcast space that anyone with a microphone is now suddenly a journalist and no one's actually putting his attention in things. So tell me about that for me, your insights in that area. So, you know, artists, people too, right?

Ernest Shaw: And, you know, success is nuanced. It's very subjective and it's nuanced. Again, we're just conditioned to see success as having a lot of money, having a lot of followers now, having a lot of followers, getting a lot of likes, a lot of clicks, you know, that as added to our definition of success. But, you know, again, it's nuanced and, you know, artists need to eat, artists need to pay their rent. If they're blessed, they need to pay their studio rent, you know, and these are hard times for everyone. You know, artists include it. And the overwhelming number of artists do not, or by certain standards, standards would not be considered successful in their field.

Whether we're talking dancers, thespians, actors, actresses, actors, musicians, journalists, you know, the overwhelming majority of folks are not going to achieve the level of success as an Amy Sherrod. Sure. You know what I mean? Yeah.

And I'm using Amy because she's very familiar with Baltimore, you know what I mean? Yeah. The over-referring majority of folks are not going to be as successful as the Joey Scott, you know what I mean? Yeah.

Or, I don't know if I want to say this, they may not be as successful as Megan Lewis or Ernie Shaw, you know, as we still push and strive to become more successful in air quotes. Yeah. Because the grind, it never, never stops. You know, they, it sounds like you see something.

Rob Lee: Yeah. Yeah. It's two things that I think of one is, and this is a quote because I frame myself as a fake philosopher, a faux philosopher. I like to call myself, I got a lot of puns now. Yeah.

But Donna, it's a lot. But the idea is, I think this grind culture will put you into the ground. Yeah. I think that's one of the things. And the other thing is just commenting back on sort of, you touching on it, I think how we deem success, right? Where a lot of times it's money or it's downloads, it's clicks. I think it's a portfolio.

I think it's diversified and somehow equated, you know, sort of attention to the currency, you know what I mean? Like, oh, you have so many likes and so I was like, I can't pay my rent with likes. Like, what are you saying to me?

Ernest Shaw: That's what I like to do. Yeah. Exactly. Yeah. That's an excellent example. Yeah. You know, so as I continue to grow and learn and accept reality for what it is, not necessarily for what I want it to be. And I do away with expectations for the most part, detach. I try to detach from expectations. Practice essentialism. What's really important. I don't like to use the word success, but I will say this. There are things I can do now.

I couldn't do 10 years ago. You know what I mean? And let's be, let's get really real. I'm breathing. We're having this conversation. Exactly. We spoke in 2022. There's no guarantee in 2025. We would be having this conversation. You know what I mean? So we're blessed. We're blessed. That is success.

Rob Lee: Yeah. That's good. I think that's, I think a thing to look at. Like earlier this year, I had one of the guests that I found on the podcast. And it really affected me.

It passed away. And you know, you do that thing and it's like, damn, I really like to do it. You know, not even from a, like, but from a humanistic standpoint. And I was like, oh, well, you know, I didn't know the guy.

I had him with Todd and it was cool and so on. But it's like, no, it's a person that's, that's, that's gone. And, and, you know, I'm overly into the thing that I do. So it's just like, that's one of my kind of friends or one of the people I've had on the thing. And it's just like, damn, I'm, you know, I hope everyone is good. I hope everything is there. So really, you know, again, looking back at that time in February, it was definitely a thing that I thought of and it started to think a bit more like, all right, when I'm thinking through this season of the podcast, what is important to me with it? It's like, I don't care about the downloads as much.

I don't care about sort of the funding is, you know, like many people lost all of my money. But it's just like, what's the most important thing? And I was like, to combat a lot of this stuff, and I'll go into it a little bit deeper as we go along.

But to combat a lot of this stuff that's noise around or noise that kind of provides framing and boxing around actually doing the thing, the way to combat a lot of it, that kind of limits it is community. What is the essentialism? What is essential to me doing this? Connecting with people, having a cool conversation.

That is sort of it. What happens after I've put it out there, after it's done? And I don't have much control over it. But being able to talk with someone, shoot the breeze for a bit, perhaps learn something, that's sort of what matters to me about the whole thing.

Ernest Shaw: Absolutely. Yeah. Yeah, I've learned a few things. One, there's no death and dying. There's no death and dying of physical death. Right. But it is important. It is a part of our socialization, how we come to understand that, deal with that, grieve. Yeah, one of my favorite sayings, and it comes from a play written by August Wilson and his fences. And I think the main character, I think his name is Troy, he says, you've got to take the crookets with the straights.

And that's one of the things I used to try to instill in my students, is you have to take the crookets with the straights. That the way I interpret that is, that's living. We are now in this anti-intellectual space. Talk about it. This space of comfort and needing and wanting to be always comfortable. We have developed, I think, a misunderstanding of what it means to live. To live is not to be happy.

To live is to experience all the things that life has to offer. Grief is one of those things. And the more you embrace love and your compassionate and kind and empathetic, the deeper you're going to grieve. So in acknowledging that deep pain and hurt, you are acknowledging and deepening your capacity to love, you just have to make that shift when you come to understand. And if that was the older you get, you're going to deal with. Yeah.

Life's child's insublations, more and more of life's child's insublations. For example, and I'll make this really quick, John Harbaugh has 17 blown leads. He has the most blown leads as a head coach and any other coach. Having said that, he's also the longest-time coach in the league. So, and he works for a very successful organization, so his team is often in the league.

So it's often in the league and you've had your job for a very long time. So, it kind of makes sense that either him or Mike Tom, they might be in the running for that. And if you look at some of the other coaches that's on that list, he's in good company.

That's not an excuse for John Harbaugh. That I'm just saying that when you add the data, you take a look at the data. So, I mean, relative to life, the longer you live, the more you're going to have an opportunity to experience some things. And some of them are going to require navigating pain in some uncomfortable situations.

Rob Lee: That's a really good point and literally the point. I made that Harbaugh point recently because I'm a data analyst. So I'm like, we have more opportunities. You're going to have more of those potentially.

And this is an aside before I move into this next question. It's almost like when you hear about medical research studies and they give you sort of the scary number, the two times rate of this incident happening, it's like, yeah, based on what? What's it that two times based off of?

Oh, 1% so it's a 2% chance, not like 50% or what have you. It's like how we contextualize it. So if Harbaugh has been a coach for almost 20 years, then yeah, you're going to blow some leads.

Maybe a season you can play with the numbers, however, but it doesn't tell the full story without sort of that context. And one of the other things that I like that you said that really, really stuck out is sort of the ease, the comfortability, the thing, that sort of piece. I think when something is made easy for us, almost don't trust it.

On my data analyst, for my day job, I use AI a lot. And I'm like, there was a point in doing this where I'm like, the questions are always my hardest part, their most valuable part, but always the hardest part during the research and so on. And it was a point where I realized the me and the questions were leaving because I was pursuing something a bit easier.

And I was just like, nah, we can't do that much further. It's like, I didn't inhale, you know what I mean? And it's one of those things that you learn from that curiosity. I think when it's curiosity, you have more sort of attempts to do something than you kind of learn from it.

You probably will fail and learn that that's not quite the way that you want to do it, but at least you got the data and the information to make maybe a more informed decision. The next step that presents itself. Absolutely. Yeah. So I have two different directions.

I could go with this next question, but I think I'll just rock with it this way as it is ordered. So I think creative work is deeper than the fun parts. And I was just touching on how much I run into so much and writing questions. So we see the productive parts. We see, you know, even the parts that we choose to make public. I know there's more sort of behind the scenes stuff. Show the process, do this, do that.

And, you know, how do you work on your art? Is it a grind all the time? Is it an experiment? It's like, oh, I can do this with it. Is it an otherworldly experience? Like, how would you describe it? Like really sort of behind the curtain because we have this persona that is always super glamorous. It's always this and it's like, damn, I messed that canvas up again. Man, I didn't even put the microphone on this time. And it looks crazy. So for you, what does that look like for you?

Ernest Shaw: I want to make sure I answer this correctly because that's a really good question. What does that look like? Currently, you know, I'm going into my second year of a PhD program. So first year, it really cut into my creative time.

It cut into my studio practice heavily. And someone who has completed the program advised me to always make space and time for my work. That that would assist me in successfully navigating this very grueling and rigorous process. It's also a spiritual journey. But the actual rigorous and grueling part, to navigate that, you have to maintain your art practice.

So I've taken it upon myself this semester specifically for this year to try and do a piece a week. Maybe some small drawings or at least it's an extended painting. Start and work on it, my painting. If I'm not doing some mural work somewhere consistently. And the reason for that is, you know, your work is what contributes to making you whole.

Right? It's it's well, let me not say your work, my work. It's a calling, right? It's not necessarily labor. And it's not necessarily a grind. In the way that we've been sort of kind of, you know, taught to understand grind. You know, grind is it appears to be, you know, it's like a hustle. And it requires a certain certain amount of grit. You know what I mean? And it just no longer feels that way.

No matter how many hours, how much sweat equity I put into my work is very, very important. Very soothing. It's a healing. It's a necessity. So it does not feel like work.

It really doesn't. It's labor, but it's not the type of labor that you do simply to make money or that you do for someone else. I think that's really where I want to go with that. It's a labor of love.

I'll put it that way. So currently I'm revisiting some old themes, some old theories. I'm recreating some theories that are consistent in my work. The times I've been most successful financially, which matters, finances matter, is the times in which I'm actually working on work. It's the times when I'm actually consistent.

You know what I mean? I'm consistently actually using my hands to create pieces while I'm writing proposals. It's times when I'll say the universe sends more opportunities. As long as I'm working, opportunities are going to come.

I get to meet people, get new collectors, new dealers, gatherers, admirers of my work. You know what I mean? And it just sort of kind of flows as long as you work. You stop working. Those things seem to, those opportunities come a little fewer and far between.

Rob Lee: That's a good point. Like when, you know, and I know this is part of your background, you know, in the last few years, you know, I've moved into sort of education, you know, doing that teaching podcast and crafting the next generation of young journalists and podcasters. Grab a mic.

Talk to Rob. And I think one of the things that when I do those pitches and they just kind of fall into my lap so the universe will have you. And when I talk to people, I do that.

They're like, yeah, that makes sense. That tracks for you. You're a person that talks to you. You're like, thanks. And but I think the thing that makes it really cool for me when I'm doing that is because I'm working. It's like, I think of, you know, sort of actors that's like, well, I'm a working actor. I'm always, I'm not a movie star.

I don't have a movie that comes out once every year and I'm doing this. It's like, I'm constantly working. I'm constantly putting together episodes and podcasts and thinking about it, going to events and stuff that's all connected to the podcast. And I think the other byproduct of having that capacity actively being in it and, you know, sort of helping folks like start their journey in podcasting. It enables me to relearn parts of podcasting that actually make me a better teacher in some regards. Makes me a broadcaster as well.

It's in some ways really reinforced that foundation. You do something for a long time. You're like, oh, I know how to do this, but if you have to revisit it because you're teaching someone how to do it, you're like, oh, I was doing that wrong for a while.

No, let's let's let's let's re-religate this a little bit. So for you, how is teaching impacted your park, your approach to art or even your outlook on like the artist's life?

Ernest Shaw: Again, a wonderful question because as an artist, I always have to, you know, I choose to take my audience into consideration. Right. And not just my audience, who I am specifically engaging in dialogue, because they those can be two different entities. Who you are engaging in dialogue through your work and who is your audience can be two different conversations. It just so happens that probably years that I've taught, much of my inspiration has come from my students and my engagement with my students.

Right. So even times when they're not necessarily my audience, they are who I am in dialogue with. I'm in dialogue with young people, the youth, even the young people who are not necessarily my students per se, but the youth and young people of Baltimore specifically.

Not solely, but particularly because now that we have technology, it can be used from anywhere. But but again, to take it back to contributing to creating your future, there's no better way to do that than to teach and engage young people because they are the future. So not only do they inspire my work and motivate me. Teaching is always a two way street.

We used to be called teaching and learning when I'm in actuality is learning and teaching because to be a very effective and effective educated, you have to first learn your students. Yeah. You know what I mean? They they come into the room as the teachers, you know, and once you begin to push and pull and learn from them and earn their trust, then the door is open for youth to make an impression, you know, and to have an impact, you know.

And it's really a beautiful thing. So that they have really motivated me and inspired me to create work in dialogue with them. Which is an extension of what happens in the classroom.

Rob Lee: Makes a lot of sense. And I had to learn that in my first. Well, I did learn of that, I suppose, you know, then my first opportunity in teaching at BSA, you know, I had like I was going to do like six months into the full year. They twisted my arm. Like, can you say I was like, sure. And and, you know, initially I was just like, all right, I can I got to talk about theory. I got to talk about how you do this and some of the and I just realized it was just like, he's a teenager, they're seniors.

It's a two hour or two and a half hour class once a week. This is an elective and, you know, always tweaking. I'm a tweaker, you know, in that way. And, you know, at a point, sort of the second half of the class or maybe the last third of the class, as far as the semester or the year rather, I was just like, let's put together some prompts, let's do exercises, let's really have studio time. I was like, it's about the reps. It's like me up here talking. I was like, you asked me questions as we're going along. And I found that that was more effective in navigating with them because that's what they value. They'd like the hands on component.

And I started looking at it. The students that I had, none of them are audio people. So me talking all of this theory and I was like, how do I connect? I was like, well, they're they're film students and theater students. I was like, we got to show the connection. It's all storytelling.

It's just how you tell a story. This is the mode. And once we got there, you see the light bulb popping off on top of their head. I'm like, yeah, it's working. This is great.

I'm not a fraud. And it was good to connect in that way and seeing just just seeing, you know, them kind of get it. That's that made me feel really good.

Ernest Shaw: It's yeah, it was a wonderful connection. Yeah, you know, it's a part of it's an example of being part of the human family. That, you know what I mean? And I don't I'm not going to go too deep into that, but that's one of my lived experiences that I will always cherish is being in company with young people. You know, it's good.

Rob Lee: So I got a couple more that I want to run by you. So I read that setbacks tend to be creativity. You know, I've kind of played with this idea for this season. You know, I, and this is the second year that I've played with this idea of really scripting down, trying to stick specifically to a season into a goal.

And wasn't quite what I fully intended. Like, you know, we have these lofty goals. It's like, ah, and really trying to adjust with, well, you're able to do it. You're able to make it happen.

You're enjoying it. And, you know, you had a plan. It didn't necessarily go exactly how you plan, but, you know, we persevered.

We ball. So when one door closes, if you will, you still have, you still want access to the room. You know, sometimes it's repelling the wall.

Sometimes it's like climbing in any window you can get into to get to that room. That's right. So because you share an experience where, you know, that mindset has been like really true for you. Like I wanted to do this. Didn't quite work. It's like, I found that little cracking crevice. It came into like the mouse hole. I found a hole in it. I got into that room.

Ernest Shaw: Yeah. Um, here's a good one. This is a really good one. Two years back, um, I was pegged, um, as one of three finalists to paint Elijah Cumber's portrait. And this was a very significant commission.

Career changing commission. This was, it was financially lucrative. It was, and talk about, it was, um, well, the winner also got a spread in the New York times.

Like it was, I was one of three and I was, it was, it was an honor to be in the company of Monica and Kagle and Jarell Gibbs. Yeah. I got a call and I put my, I mean, I put my foot in this kind of shit, right? I mean, I'm not, I cried.

He is, right? Uh, yeah. The day I got the call, it was a Saturday. I was in my studio and, um, I didn't get it.

I was crushed. And this was just a few years ago. So I'm older now.

Like, you know, all that talk about detachment, meditation and, you know, alongside that, right. I was ever stated. I really wanted that. Um, and thought I deserved it.

So I sat in my chair and I said, look, you know, your process when you're disappointed. See, he is so go through it. Don't call anybody yet. Chill. Relax. I mean, just go through it. Do your thing. So I go into this, you know, very emotional process. About 10 minutes in the phone rings.

It's Dr. Leslie Kingham and she says, Hey, Ernest, we're selecting you to paint a portrait of Thurgood Marshall. So you talk about an emotional roller coaster. Yeah. Yeah.

Would I have like, would I have liked to, to get both commissions? Yeah. But chances are I would not have been able to put my best foot forward because that's, that's a lot of work.

So that may not have worked out. So, you know, you know, now I'm like, wait, what? So within 10 minutes, you know, within a blink of an eye, your life can change.

Yeah. You know, and before I had a chance to call and tell my wife what I didn't get, I was presented with an opportunity to call and tell her what I did get. You know, so it was a quick reminder to always count your blessings.

And what's for you is going to be for you. I was very happy for Jarell and Monica. Yeah. And I've learned to celebrate other people's victories because it's a victory, it's a victory for me too.

Yeah. You know, whether we talk about Mama Joyce, getting that big, that huge show, that retrospective at the BMA and then it going to, I think Seattle was like, that's a win for me. Well, we're talking about Amy Sherrill telling the Smithsonian now, that's a win for me or us rather. That's a win for us. You know, Jarell's show at the Brandywine is coming up.

I think Angela Currell contributed to that along with a few other people. That's a win for us because we all in this together. You know what I mean? When you think about it, when you really think about it, we're a community.

What does community mean? But yeah, I went through, I went through as my administrator, you know, struggling with those crookies, taking the crookies with the straights. But I think that I think when I think back in recent years, that's a good example. Yeah. Of, you know, yeah.

Rob Lee: That's a good example. And then it's funny, this season, you've come back on, Monica's come back on, and Jarell. So yeah, you know. Right. Right. That you haven't.

Ernest Shaw: I thought you tapped it. I mean, clearly you're doing what you're doing something right.

Rob Lee: But it's really great. And to sort of hear that real life example, and thank you for sharing that because I think, you know, folks don't really know what's really happening behind the scenes and what a situation could look like. It's like, hey, you get everything that you aspire to get.

You are able to get every, in my instance, every interview you want or every guest you want and so on. And, you know, sometimes it feels like it's that cycle of like elves, you know, but eventually it's not really a cycle of elves. And it goes back to that piece of what does success look like.

And I've deemed it and I feel this way. Sometimes I have to remind myself, but I feel this way that if I'm able to keep going and if I'm still interested in curious about it, you know, maybe having those those crickets, if you will, isn't as bad sometimes because at the root of it from an essential standpoint, I'm still able to get the interviews that I want. I'm still able to have the conversations that I want. And at a minimum, you know, someone's getting something out of this and they're listening to it and hearing really dope insight from you.

Hearing me fumble through my words, but getting really dope insight from you. That makes it just worthwhile. That's beautiful. So I've got two more questions here.

I want to run by you. So this came up recently and I touched on it a little bit before we got started. So let's talk about goal setting and setting intention. You know, I learned you have like a meditation practice, supposedly a daily meditation practice, but so let's talk about how let's talk about that, the meditation practice and how, you know, how intention shows up for you. Like I read that our goals come from either inspiration, or the intention or desperation a lot of times. And sometimes you misidentify them. So I think where does inspiration come from for you? Where does sort of that setting intention play a role in that? Oh, man. Yeah. Happy to share.

Ernest Shaw: I'm more recently, very recently, and beginning to embark on a practice that intentionally venerates ancestors. Right. What that means is for me. Develop a more rich and intentional relationship with my ancestors. In doing so, I am. Exploring. Around that could easily be ignored.

What do I mean by that? Each day early in the morning, I'm a morning person very early in the morning. I spend time specifically with my older brother and my son, who are both ancestors. And this new journey, this intentional attention placed on ancestors has opened up my consciousness in ways it has not.

I mean, it's because it's intentional, the intentionality involves. It's changing the way I see the world and the way I see life. Through meditation, especially. And the most simplest way I can say that is mindfulness. Well, I meditate in the morning, but that meditation allows me to be more mindful and aware throughout the day. So it gives you, it helps you fine tune a practice of an intentional awareness of more than just what's happening on the surface. Does that make sense?

It does. You combine that with the mind. You combine that with some ancestors, narration. So you're getting more in touch with some, I'll say, some resources or some sources. That help guide you.

That's where I'm going with that. We talk about inspiration, talk about ideas. We're talking about asking for advice and guidance. It's a way to help guide me. I might have spoken earlier about finding your group. It's a way to help you get exist in a space where you can you can vibrate on a frequency that that is again beneficial to developing good character.

Again, another goal. You spend more time with your ancestors, not all the ancestors, but some of the ones that can help guide you. It will assist you in developing good character. And if you get into a space and you're vibrating from an intentional space of attempting attempting to develop good character, then you the universe will send those will send things one to test you to make sure you are sincere.

But also. Not reward, but to surround you with, you know, the law of attraction, like with karma, you know, all of these things are related, so to speak. So I don't know if I really fully answered the question. But I. I did want to highlight that the meditation practice is tied to answers. Make some generation and focusing and being intentional here.

Rob Lee: It does make sense. And here's the thing, though, right? Sometimes it's it's a if the answer is is loading. And I think there that is an answer. I think that sort of here's my thoughts or my my comments in that area right now. There's no verses like here's the direct answer. This is exactly what it is.

It's like, no, this is what I'm what I'm working through, what I'm processing. And I think. In doing this and making it a point to especially when I have someone who's been on the podcast before, we've seen each other in IRL before as well. And, you know, just sometimes it might be the same question, you know, a year later, two years later, what have you in the process of the question. The answer to that question might have a little bit more depth into it.

It might have a different sort of texture to it. So I like that sort of in process answer. This is where it's at at this moment. So here's the last sort of real question. And then I have a few rapid fire questions for you, but here's the last one.

And I have to talk about sort of that IRL of it all. So one of your murals, one of your works is outside of my office at work and my day job. And so I get to see your work all the time. And I get to also, you know, look at some of the students who did that. I'm like, that's my man.

I just did that. And, you know, I'm amazing sort of the students and the visitors really like captivated, you know, by your work. So what do you hope people experience or feel, you know, when they're in front of your work, when it's out there, you know, just to be consumed, to be appreciated? And I think it's a good sort of pinning to it as you touched on like who you're speaking to and who's your work for or like who's an appreciative of it and all of that good stuff. But sort of, you know, what are your thoughts in that area?

Ernest Shaw: So mural work is slightly different than studio work. Yeah. Because you are intentionally creating something that you don't just share with the community, like it becomes, the community owns it.

Right. So, and there's a lot of power that can be associated with that, you know, mural work. So one of the things I want folks to experience when they experience my work is, you know, the definition we've been given of what it means to be human has been given to us by people who have done the most inhumane things of record. You know, I'm not going to go too deep into that.

But if you look at simply the history that we're taught in schools, which is which they wrote, it's their history. The dehumanizing of others is one of the most inhumane things you can do. But yet that is the foundation of our definition of what it means to be human. Through my studies with my PhD and in my artwork, I'm seeking to contribute to a shift in that thinking.

What it means. So I want people to explore what it means to be human in themselves by witnessing the humanity of my subjects and my subjects more often than not. People who have been considered public nuisances, castaways, the wretched of the earth.

You know, people who are families or members of marginalized communities. So if you can see the humanity in my subject matter and those figures and portraits, the only way in which you can do that is if you have that humanity in you. So it's an opportunity to develop a relationship with, so there's more than just paint on a wall or it's more than just a piece of artwork.

You know what I mean? You're developing a relationship with yourself. It's really a mirror. I'm holding up a mirror to the viewer, to the audience and say, who are you really? Right? Yeah, I think that's the best way I can answer that question.

Rob Lee: That's exactly what I say to them when they're standing there. They're like, oh my gosh, who did this? It's like, yeah, it's a mirror really for you. Say those exact words in that same way. You know, so thank you for that.

That's really, really good. It's a lot of times it's the invitation and then doing this and sort of how I curated it. I try not to be too on the nose with it, but you know, one of the themes has been running for this season is stories that matter. And I naturally came to that because it's not sort of who's the biggest person, who's the biggest name. It's like who I am is reflected in who I'm having to come on, who I'm interested in sort of who I'm interested in talking to and sort of how the conversations go with how they're structured. You know, I can have a conversation with someone who is a chef or really in the foods and we have a deep conversation about it.

We're having a more esoteric brain-milting conversation about how it works in the universe as well as the work. So, you know, and this is not, this is not, this is not done on purpose. I didn't stage this, but before I get to these rapid fire questions, I have to, you know, put on something real quick. So I had to put on a mic hat as well.

Ernest Shaw: And, uh, it was literally just put in headphones. All right. That's fine.

Ernest Shaw: No, today was the day.

Rob Lee: So I got a few questions for you from a rapid fire standpoint and they're quick questions. One is a little bit longer, but they're generally quick questions. Um, I'm going to hit you with the quickest one. What is your preferred name for Baltimore? Is it Baltimore? Is it Baltimore?

Charm City? Be More? What's your preference? It's Be More. Okay. It's Be More. Um, that works. Uh, here's another one. Uh, Baltimore has so much iconography, I think, you know, where, you know, it's often, and like we have so much iconography here in the art, sometimes gets overlooked because there's so much there.

It's like, wow, I'm seeing so much overstimulation and all. What is a symbol that comes to mind for you when you think of Baltimore, like macroly speaking? Some people say the skyline and a harbor or things of that nature. But for you, what is that symbol that, that symbol right there? Oh man.

Ernest Shaw: I'm thinking architecture first. But, um, maybe when I was a kid, maybe the shot, but, uh, the Washington monument on Charles Street, and if we're talking, if we're talking buildings, uh, Key Bridge. Yeah.

Rob Lee: When I was, yeah, when I was younger, uh, so you talked about it earlier, West Baltimore originally for me, Argo Avenue and all, it was, it was the Billie Holiday statue for me.

Ernest Shaw: Oh yeah. Oh man. My cousin sculpted that to James. Oh, Pennsylvania Avenue. Bluff yet, Pennsylvania and Dawson. Oh, that's, oh, that's a good one. Let me go back. For me, this, but this mural no longer exists. There used to be a mural of checker players. An old gentleman, black can be defined as black. Oldest gentleman, maybe a gentleman in his mid 30s, early 40s.

And then a young kid standing there watching them play checkers. And it used to be on, we're popular Grove and Emma's Avenue and Franklin Street met. There used to be a bakery there. And every day coming home, going to school and coming back, I would look at that wall, I would look at that on the bus. I would look at that every day. Um, that wall is the reason why I became a mirrorless. Wow. For me, so for me, that was a symbol of Baltimore.

Older gentlemen, man, young child studying and watching them play checkers. That, that tri-vector, that, that Trinity, um, that mural sang and, and, and, and it says the pictures worth a thousand words. The narrative associated with that really sums up much of my lived experiences in Baltimore. Great question. Wow.

Rob Lee: Thank you. Um, this is, this is the last one that it is. No, you don't need to even belabor it. It's the last one. So as we look at sort of, we're in, we're in Q4 wrapping up sort of this year, the, oh, before it's done, you know, August, disappear, September is almost over. Um, so you, looking at 2025 thus far, what's, what's been the biggest highlight for you professionally? Like as an artist, um, what's been the biggest highlight for you? Should I spill the beans?

Ernest Shaw: Um, I've had an opportunity to work in tandem with a close friend of mine on some redevelopment projects that's going on in the East Baltimore, specifically Old Town. You're talking about my old neighborhood, okay? Yeah.

You know what I mean? So Old Town, um, Dana Henson and her development company, they're putting together an amphitheater and outdoor jazz walk, uh, to go along with the other development and murals from other artists and things that's, but they really redevelop it in that, that part of town has been a long time coming. And, and, and it's just really a blessing to, to, to be able to contribute, to continuously contribute to not just beautifying, but because there's some educational components associated with this project as well. Um, and jazz is playing a large role in that. You know, so that's, that's probably the biggest project I've worked on this year. But, um, yeah. And also being commissioned to pay man brander sky. Nice. You know, I think that might have been launched in 2024, but yeah.

Rob Lee: Had a, had a little behind the scene conversation about that. If I would have heard a little bit about that. I have my tentacles everywhere. So this is, this has just been, um, great. And I appreciate you coming back on and, you know, I think it's a good space for us to sort of close out on the conversation.

So, you know, there's two things I want to do. Um, one, again, thank you for really, you know, adding some like thoughts and values and insight to this, this conversation and to this part of the season. Um, and coming back on. And secondly, I want to invite and encourage you to share with the listeners anything that you want to close out on. Um, usually it's the shameless plugs, but I'm leaving it open. And so if you want to, any, any final thoughts, any, um, anything that you want to say, any final moments, the floor is yours. This is going to sound a little corny,

Ernest Shaw: but as I get older, um, corny is not bad. Acts of kindness is what's needed. I remember I was asked to speak very briefly to some BSA students a few years ago and mama Maria Brune, she said, can you say something about kindness? Um, acts of kindness. However you choose or feel compelled to do that. I employ, I'm begging your audience to, to begin to think about that. You know, and, and, and act on that. And I think I'll leave it, leave it there.

Rob Lee: That's great. Really timely. That's always timely, thoughtful. And yeah, I think, um, it's good.

Ernest Shaw: Thank you man for continuously doing, I'm fairly impressed. Of the work that you're doing continuously doing and the ways in which you've grown since the last time we talked. Keep doing what you're doing, brother.

Rob Lee: And there you have it folks. I want to again thank Ernest Shaw for coming back onto the podcast and running it back with me. Truly a great conversation and really happy to reconnect. And for Ernest Shaw, I am Rob Lee, Santa Fe's art, culture and community. Ending around your neck of the woods. You just have to look for it.

Creators and Guests