Restoration Carpentry, Miniatures, and the Art of Preserving History with Matthew Hankins

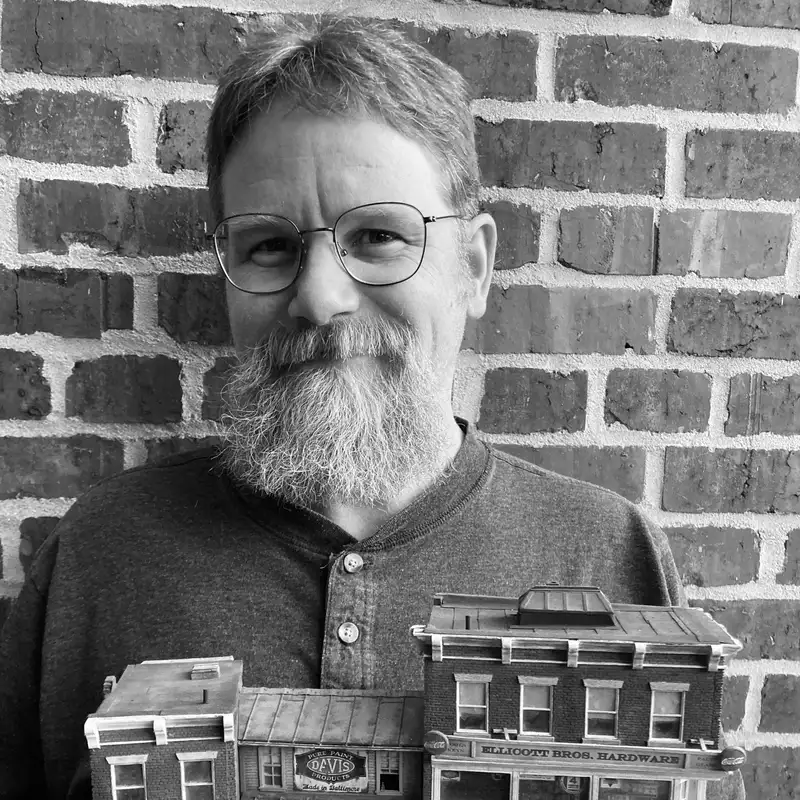

Download MP3Rob Lee: Welcome to the truth in this art. I am your host, Rob Lee. And today I am privileged to be in conversation with my next guest, a restoration carpenter, historian, collector, maker of models and a miniaturist who was inspired by a diverse array of structures of his hometown, where he creates row houses, factories and shops at a one to eighty seven scale, imbuing them with detail and realism. Please welcome Matthew Hankins. Welcome to the podcast. Thanks for having me. It's good to be here. Thank you for coming on. Thank you for making the time. And, you know, we were able to chat a little bit. It's good to chat with folks before you get into the dance monkey thing. Like, here's a bunch of questions I got answered. And so starting now, before we get into like sort of the main event or the main course, if you will, I'm going to go into the sort of appetizer questions to starters. Could you tell me about your background, a little bit about yourself and maybe your first experience you know, experience with art, creating, tinkering, things of that nature?

Matthew Hankins: I was born in Baltimore, but raised in Carroll County on a little farm in Hampstead. And yeah, just, you know, fairly typical growing up in the county kind of deal. As far as art is concerned, I grew up surrounded by art. My father is an artist. He taught art at a couple of private schools and public schools in the area. And his background is pottery. He's a potter and makes and sells pottery, dishware, and all that kind of stuff. And my mother, was a drama teacher. And so we did stage sets. And my father built all the stage sets. So I go and help with all that kind of stuff. He taught art. He taught woodworking. All kinds of friends. He would do his pottery and set up the kiln and fire the kiln. And people would come and participate. We had visiting artists. All of our family friends are artists, so fiber artists, fine artists, the whole nine yards. I grew up surrounded by art, but I was not an artist. I was sort of the black sheep. My sister's a super talented artist. And people would ask me, you know, you get together with friends and family and things, and people would say, well, all this talent in that family, what do you do? What is your art? And I said, well, you know, I always used to joke, somewhere around my elbow, all the art leaks out. I can see it, I can visualize it, but it can't quite make it to the paper or the canvas because somewhere around the elbow, all the art ability leaks out. And so I wasn't… I wasn't an artist. I never considered myself an artist. I sang. I sang in a church choir. And I made things. I was a maker. I'm a carpenter. And I got into woodworking and carpentry and historic preservation and restoration, did all that kind of stuff. But that was never considered art. And it's only become recently that I have just kind of discovered, if you will, that I am an artist. And most of it has come by redefining art, right? By by by telling myself, well, the the the craftsmanship that I do, the the making that I do, the music that I've done, the cooking that I've done, all of these various different things are a form of art. Specifically, I'm doing miniatures. I've always been into model trains and doing models and miniatures and things like that, but it was always modeling. It wasn't art.

Rob Lee: So, and we're going to go, we're going to go into that deeper. I don't, cause you're going to give me the whole thing. You're going to give me the whole thing and I don't want the whole thing right now. Um, but, but, but definitely thank you. Thank you so much because I think starting off, like it's, it's really interesting to have a comment on that actually, um, in, in doing this podcast and doing it for as long as I have, like, you know, it's about 600 episodes at this point and podcasting for 14 plus years at this point and talking to people who are art critics, curators, people who are artists. And, you know, this sort of notion, this redefinition of it, this you know, kind of diminishing the rarefied nature that's usually associated with art. It opens it up a bit that, you know, people just ask the question, are you an artist? And you just kind of go from there. It's like, how do you define yourself? How do you perceive yourself? And, you know, always kind of look at it like, And I was looking at some of your work. I was like, wow. How do you do that again? How is that done? And I was like, I can't do that. And I was like, this guy's an artist. And that was kind of like maybe one of my rubrics, if you will, of like, can I do that? No. Artist.

Matthew Hankins: Well, but but it also it's so important. to have that creative outlet, right? I mean, you know, so many of us get up every day and we go to work and we, you know, we crank out a spreadsheet or we, you know, we produce a report or we do all these kind of things and you go to work and you have your family and you work with them and you do things with them, you do all this different stuff. But having that creative outlet, I think is just so important. And, and everybody's capable in some way of doing it, whether it's poetry, or, or baking, or knitting, or whatever it is, creating something, it feeds the soul. Right. And so Because of that, because I've been able to find my piece of art and recognize it as that, I think that's been super important for me. And I think it's super important for others who don't consider themselves an artist. An artist isn't somebody who can paint a recognizable face on a canvas. An artist is somebody who creates something. And it doesn't even have to mean anything to anybody else. It's really creating something for yourself. So yeah, it's yeah. Figuring that out was a big thing, because like I said, family full of artists and I wasn't I wasn't one of them.

Rob Lee: I hear you. I like that. I'm going to steal that from you. It's like, yeah, you know, all the talent I have just goes right out of my elbow. It's just here.

Matthew Hankins: That is like that.

Rob Lee: So so how did you touched on earlier having something like this, this early interest in like model trains, miniatures and things of that nature? I remember when this is not quite related, but I remember I had this this kick where I was into watches and model cars, and that's what I was doing. It was just bought a new watch, buying this like 1985 Corvette model that I'm going to paint and do the whole thing with. And that was like, I feel like this is eventually going to go to planes. And I was like, I'm going to have a conductor's hat on soon, aren't I? So so stepping back, how did you first get into like miniatures and tell us, you know, how did you first get into miniatures? And so I got a carpentry question next, but I want to ask about the miniatures.

Matthew Hankins: So, so my father did model trains, so it's pretty typical, pretty typical sort of model train story, right, you get into model trains because your dad was in the model trains and dad would set up the train. And he had a layout, and he would set it up, he's only I think we only set it up once it weighed a ton it was all. It's a big sheet of plywood with paper mache all over it. And we kept it in one of the outbuildings on the farm. And we brought it into the house a couple of times, and it was just a monster. But we built a number of layouts through my youth. We had a coffee table with a layout in it. We built some layouts at school when he was teaching at the school I went to. So it all came through him, this model train stuff. And we were horrible model train people. the trains never quite made it all the way around the track, and the wiring never quite worked properly. But we had a blast, right? We had a great time, but we were not very good at it. But that was kind of the introductory. And then through that, sort of leading to what you were going to talk about there, is that I'm a building fan. I'm a huge building fan, uh, old buildings in particular. And so the train thing, while it's still there and I still have trains and I still have track with wire in it. And my trains do actually now run back and forth. I've had more success with that recently. But the buildings are what I'm into. And that's where, again, the shift happened into I really enjoy making the buildings. So now I'm making the buildings more than I'm making the trains.

Rob Lee: That's great to be able to, you know, kind of try a litany of different things and have that sort of early experience and see, you know, taking taking off from, you know, maybe where you were getting some like influence from your dad and figuring out for yourself like, all right, this is actually the direction where I want to go and this is what I want to try. And I've done a few. interviews around like, you know, historical buildings and I had this like week of interviews with architects and that a lot of their work was around like taking these these buildings with quote unquote good bones and then it's like how can we bring this into how can we modernize this and this sort of modernization and restoration approach. So definitely buildings are something for me. And I think even when you go to certain cities, always look at the architecture, like what what denotes, you know, what kind of buildings are here, what's what's here, what's what's here from the past, things of that nature. And so talk about how you got into to carpentry, though, as I want to hear a little bit about that, like that restoration carpentry work, because I've you're like the first carpenter I talked to, which is six hundred episodes.

Matthew Hankins: Yeah, so well, so I was always into two buildings and that kind of stuff. And again, you know, you grow up on a farm and you do a lot of, you know, fixing of things and work building things and working on things. And, you know, there's that. I think everybody goes through an architecture phase. I'm going to be an architect. Right. Everybody at some point in their life decides they're going to be an architect and then they're going to be a veterinarian and then whatever keeps kind of progressing along. And I wanted to be an architect. And then around middle school, fifth grade somewhere, I discovered Old House Journal Magazine and discovered that there was such a thing as restoring and preserving older houses. And that was it. That was the thing. I loved the old buildings. I loved the details, the woodwork, the masonry, all of the imagining. I loved history. So it combined a love of history and a love of architecture combined into being a historic preservation focus. And, and then I discovered that you could get it, you could get a degree to go to college and get a degree in historic preservation. So that's what I decided to do. And I went off and got my degree in historic preservation. And I took all the classes, the law classes, and the planning classes, and the, you know, conservation classes and all this stuff. And in college decided I wanted to I wanted to touch them. I wanted to work on them. I didn't want to talk about them, I didn't want to fundraise for them, I didn't want to manage them. I wanted to work on them. And so I went to the North Bennett Street School in Boston, which has a historic restoration carpentry program. And I spent a couple years in Boston learning the trade. And that was great. It's like an apprenticeship leap, jumpstart. You're learning it. It's a two-year intensive class and course on historic restoration and carpentry. And it's It also comes, as a lot of those programs do, with the cachet of the name. So you just mention that you came out of North Bennett Street, and people are like, oh, you must know your stuff. So from there, I was able to go to a museum in New York City and work in a historic museum village for a number of years and work on buildings that dated from the 17th to the early 20th century. I was a caretaker for a 17th century house, the third oldest house in New York City. And then we we had our first daughter and decided I decided I wanted to be closer to home and closer to the support network. So we came down here and I worked for a residential company for a few years. And then I've been working for a commercial restoration company since then. And I manage a 10,000 square foot restoration mill shop. We're cranking out hundreds, if not thousands, of restored windows a year with my crew. Windows, doors, trim, restoring, fabricating, replicating, whole nine yards. And it's something, man. You get to go behind the velvet ropes. You get to touch things. Some really awesome, awesome stuff that you get to do.

Rob Lee: Well, you were describing some of the some of the items you and your crew work on. Oh, happy. I thought I thought you were starting to do a jingle. And I was just like, I was like, yeah, right.

Matthew Hankins: It's a commercial. Yeah. No, it's it's cool. I mean, we've so we've worked. We did the we were the primary masonry contractor on the Washington Monument in Mount Vernon. We've worked on the Walters Hackerman House. We did all the window restoration in the Sagamore Pendry Hotel. We have worked on Basilica. We've worked at multiple Johns Hopkins. It's funny when we drive around town or whatever and my daughter points out a building and, oh, look at that. I say, oh yeah, I worked on that. Oh, of course. Of course you did. Of course. You probably worked on that one over there, too. Well, yeah, we we looked at that one. We never we didn't get the job.

Rob Lee: But, you know, it's like, you know, I do that when it comes to interviews that I've done. I was like, I interviewed them. It's cool. And that before it caught me for these tickets for this thing. Yeah. And it's funny, like some of the places that you mentioned there, I've either been there or I have a relationship with some of those places, like definitely I've been to Sagamore, stayed there a few times for these sort of staycation. It's it's it's weird. Like for me and my partner, it's become like a birthday spot for us. It's like, oh, well, you want to just like drive down, take an Uber from your house in like, you know, Mount Vernon and just drive down to the Sagamore. It's like it's right there. You know, the room, you know, drop your $800 and just enjoy, you know.

Matthew Hankins: Well, last time, last time I was there, there was still dirt floors and, and the windows were still getting installed. So it's been a little while for me. But yeah, it's a great, it's a great building. And it's and I'm, yeah, I'm always pleased, always pleased to see a building like that get a new life because that that building sat down there with all boarded up for a long time. And it's it's really great to see it, you know, hop in and a big, big car. I guess so. Yeah, it's it's neat. It's, you know, next time you go next time you're in the in the Sagamore, check out all the all the big old wooden windows and you'll know I know a guy who worked on this.

Rob Lee: It's going to be real funny. And you're like, so, Rob, and by the way, just just to give you the visual, right? I'm six four. So it's like, why is this big dude just staring at the windows here? I'm trying to figure something out. It's like, yeah, Matt, you've worked on these. Who?

Matthew Hankins: You know the guy. That's my whole life. You'll go on a, we'll go to a museum and I'll, I'll be pressed right up against some paneling or something like rubbing it and checking out. I wonder how they got that to go to get right, you know?

Rob Lee: So I would, I would imagine that, you know, you know, I definitely want to dive into the miniatures a little bit. And in that work, that's that's one of the thing that really has my interest. So talk about having, you know, some of this background, this education, this experience in restoration and going, you know, and being in these places that just have really like great name recognition and a long lineage and history connected to it. How how did you turn to this like avocation of of I use your word, by the way, avocation of working on miniatures to the degree that you're working on now. Like, how did you start? Like, talk about that. Talk about the process, because I know nothing about that sort of process. I'm like, yeah, someone just drops it off and he paints it. How does that work?

Matthew Hankins: So so I started, you know, when I was doing Model Trains, you can buy building kits, right? Just like you buy model car kits, model airplane kits, you buy model building kits. And generally, when you start out, they come in plastic, and then they have what they call craftsman kits, which come in wood and plaster and metal and all these different materials. And so you buy these kits, and you assemble them, and you paint them, and you put them on your train layout. And After a while, I wanted something to look different. I wanted my buildings on my layout to look different than other people's buildings. And I know buildings. I love buildings. I'm in them all the time. And I would look at a kit, and I would say, that's great, but it's not quite right. They wouldn't really do it that way. That doesn't make sense structurally. And then also, I wanted to look different. And so I started scratch building is what they call it. So you're, you're, you're buying the rough materials, you buy the wood, you buy the, you know, the plastic and plaster and paper and all this stuff. And then you design it and cut it all up and build it yourself. So you're making your own kit, and then making the building from it. And it's, It's not easy. It's not easy because when you buy a kit, it's all laid out all the windows and door openings are cut for you, you know, and and everything's planned and designed and you just assemble it and the leg up that I have. is I know how buildings go together and so now I can take these pieces of wood and I know how to lay out the windows so they look like they're in the right spot and how to, you know, construct something that looks realistic and doesn't look sort of off in some way. And so, yeah, I mean, ultimately what happened was I wanted to make things that looked unique for my own layout. And so I started honing my scratch building skills. And then eventually I got to a point where I could build things, specifically Baltimore things, because that was the area I wanted to model. And the city just inspires the hell out of me with its architecture. So yeah, so I just started building Baltimore specific scratch built stuff, which you don't, you know, when you're modeling, you can't necessarily go out and buy a whole bunch of Baltimore row houses. You can actually, there are people who sell kits for Baltimore row houses, but there's like one of them. It was like one kit. And so, yeah, so it was about being unique, building something that nobody else had. So, I mean, that was sort of the impetus for it. And as far as the process, it really is about, first of all, being inspired by something, either you generally are not building something that exactly replicates an existing building and building something that sort of borrows from a lot of different things. You know, row houses are great because they're all the same, but they're all slightly different, which is awesome. And when you build one, there's some things that make them distinctly Baltimore. But yet, if I, so if I have one of my row house models and I show it online or whatever, the Almost everybody will say, or a lot of people will say, oh, that's Baltimore. I knew it as soon as I saw it. But then you'll get a few people who say, oh, that's Philly, or oh, that's St. Louis. But yeah, it's just, I don't know. I'm rambling again. I'm glad you kept his rambling.

Rob Lee: No, no, no, no. I think I think that's that's that's really good. So I'll I'll help and direct it in this way. And and I think you definitely gave a lot there, because like I said, I knew nothing in that area. And I would imagine a lot of folks listening to this was like, oh, wow, that's what that process is. That's what it what it's like. So. Talk to us about like sort of the time that goes into it, because I would imagine like I have like giant hands, right? So like painting models and painting something to the scale in which and tell us about the scale as well. But painting something and working on something in the scale in which you're working. I'm just like, I'm going to throw this. I'm just this is going to get knocked off. It's like just Godzilla's here. So talk about, you know, like how long that process can take, you know, like what that range might look like from conception to like, OK, I want to do a model on this from scratch modeling to something that's more so like complete and it's finished. Like, what does that like look like and what is the scale and the scope in which you're working?

Matthew Hankins: So Generally, I'll have and I work on projects of various different sizes. But generally, if I'm working on, say, like a pair of row houses or something, I will sort of have in my mind what I want it to look like. And largely, that has to do with topography. Like, do I want the row houses to step up in a certain direction or what have you? Or are there going to be on a corner? You sort of figure out your design, if you will, your inspiration. And then so I get a laser cut brick sheet. So the brick is already cut for me. So I don't have to cut each individual brick because that would be insane. So, so I buy this brick and then I can I also use window castings plastic window castings generally sometimes i'll do scratch windows and doors but largely do the plastic ones and so what you're you're basically doing is just you lay out on the brick. where your window and door openings are, and you cut those openings out. And then I'm doing things like scratch building cornices, scratch building the bay windows, the big metal bay windows you see all over Baltimore. Marble steps, put marble steps on there, you gotta have those. All these things, all these little components are slowly getting added on top of it. So I wear a magnifying optivisor, right? Because my eyes aren't that good. And it's just a lot of model paints, acrylic model paints, learning the techniques to replicate what brick should look like, what cement and concrete should look like, what asphalt looks like, what asphalt roofs look like. So I paint everything. And then the final step, the one that really makes it, is that then I weather everything. And people will notice when they look at my work, my work is generally very heavily weathered, which means that it looks old and worn and dirty. And what that does is it does two things. One, it hides flaws. The weathering is a spot that I can hide flaws. I can hide flaws with weeds and bushes and bits of newspaper. I can hide them with dirt and grime and all that kind of stuff. So it hides those flaws. But then the second thing it does is it creates that scale. So my scale is 1 to 87 or what's known in in model trains is HO scale. And so a typical person, you know, would be about three quarters of an inch tall. And so what happens is if you paint that with model paints and it looks really great, it looks like a toy. But once you add the weathering, What happens is it gives atmosphere. So when you're looking at one of my models, you're always looking at it from a distance. And so the weathering creates that atmosphere. You're looking through a haze. So everything dulls down. Everything looks a little bit muted. And it makes it look more realistic and less like a model when you put that weathering on there. And then third reason, I just like the aesthetic, right? I just like, I like the look of these sort of worn and beat up and, and, you know, but, you know, sometimes they're completely decrepit, and sometimes they're just looking well-loved, right? So, but, but, but everything gets weathered. Even the people, if I put little people in there, they usually get weathered. The cars usually get weathered, because it just, it doesn't look right if you don't. So that's sort of the, that's sort of the whole, The whole process is you start with a your design and you end by by throwing dirt all over it.

Rob Lee: Thank you. That's, that's great. And, you know, it's not it's not the same but it I started thinking of. these these guys that will take maybe reference and they'll take like, you know, what is it, a proxy, what have you, and take reference from like, let's say, action figures, but not like toys, but something to like a higher sort of scale or have you. It's like, I'm going to swap this out. I want to add this level of realism here. I'm going to actually paint. And then I'll see them weather it and they'll compare what they've worked on, what they spent time on to like what the source material was. And I was like, this is night and day. That looks like a toy. This looks like a model that you made. And yeah, there's some artisan thing here. And now you can charge this rate or whatever it is, because the people are taking commissions. But it's something to kind of see. this looks right as it's weathered. Like, I need to see the stubble. I need to see the dirt. I need to see the grime on the purse. That's what people have.

Matthew Hankins: Right. Well, and it pops. So that weathering helps pop details. Right. You do you do washes and things. And suddenly, especially, for instance, on figures like that, you'll do a wash. And the and, you know, there's a lot of those a lot of those sculpts and castings for action figures and people. I mean, they're super detailed. but you can't that all is just molded in one color plastic and that's it. But you throw some different colors on there and you throw washes at it or you paint it and define it and suddenly it's just that original sculpt is just fantastic. So yeah, it's pretty cool. I enjoy all aspects of You know, all right, history, old buildings, and little tiny things. I like those three, right? But people are fascinated by miniatures, right? They love seeing something they recognize, but making it really small. And it's cool to see that, you know, all those things. There's a lot of really talented miniaturists and model makers out there that are doing this kind of stuff. But yeah, the weathering is super key, in my opinion. Otherwise, it looks like a toy.

Rob Lee: So I got one last real question and then I got like four rapid fire questions. So this this last one, I'm just kind of bringing it home. And since we're definitely talking about process or have been talking about process, I want to dive into, you know, you can either go in this direction or go most recent. But. you know, tell us about one of your favorite projects or one of your most recent projects. I know people get real caught on. I don't have favorites.

Matthew Hankins: It's like, all right. Yeah. Yeah. Sometimes the favorite is the last one, right? Whenever the last one was the favorite. Yeah. Yeah, I. Yeah, it's hard. I would say, so I did last year, I think, I did a model of a diner based on one out of Star Wars. And that just tickles me every time I walk past it, because as a kid growing up in that time and having all the action figures and playing with Star Wars, the idea that I made something out of the universe that nobody else has, it's kind of fun. And so I enjoy that. And then I think as far as my, my, like my favorite Baltimore centric, I love the row houses. I enjoy making the row houses, but I made a pier, the light street pier, which used to stand down where the light street pavilion of Harbor place is. It was a big giant pier down big wooden pier where the ferries would go back and forth out to the Eastern shore and down into Norfolk and that kind of stuff. And I built that. And That's another one that I enjoy. I enjoy looking at it again, passing by it and seeing it. It's very, it's big. The whole thing is like 18 by 14 or something like that. It's a big model. And it's all the way around. I did the whole, it's not just a facade, I did all the way around. So the pier going out in the water and I had to I had to sort of make it up. I had some satellite, not satellite 1930s, no satellites 1930s, some airplane photos from the 30s that I was able to reference sort of the shape, but I sort of had to make it up, which was fun because then I could create something and not feel locked into making it the way it was. But that one's really, I do enjoy that one. And every now and then somebody posts a historic picture of it and I, every now and then I'll shoot off a photo of my model. that.

Rob Lee: Don't forget me. Yeah, right. That's that's great. So thank you. Thank you. Thank you. And that's kind of the conclusion of the real podcast. Now it's time to get weird and ask, like, just just random questions. But I'll give you the the disclaimer that I give everyone. Don't overthink it. Whatever you say is what you say is like this. This is what I believed in the moment. This is what I was going with in the moment. All right. So here's the first one. Imagine that you can instantly learn any language. Which language would you choose? French. OK. I've heard someone who is a native English speaker and was like, English? I was like, that's really funny, actually.

Matthew Hankins: Yeah, I say French, maybe Spanish. See, now I'm overthinking it. Spanish would help a lot at work, right? It would help a lot at work. I mean, I do OK. And my the people I work with are phenomenal and very patient. But French, because I don't know. I'd like to go to France and speak French. I don't know why.

Rob Lee: It'll help you with ordering. It'll help you with ordering food. And so this wine would be great and just say it should be classy.

Matthew Hankins: I also feel like maybe I'd get by a little better in France, you know, instead of being an American in France going, you know, stumbling my way through it. But, you know.

Rob Lee: Can I get a crescent?

Matthew Hankins: Sorry, you have to leave. No, yes, no. Sure, you have to leave. We can't do this anymore.

Rob Lee: You got to go. I think it would be Japanese for me. And that means I'm relocating. That means I'm now living in Japan. Right, there you go. Not a huge population here in Baltimore. If you could travel back, you know, tickling the historian note, if you could travel back in time for one day, when would you go?

Matthew Hankins: Oh man, now you're hitting one that this is one that I think about all the time, right? Time travel is like, what a great thing that would be. I believe that it would probably be the late 19th to the turn of the century. There's a There's a time period there where America was really booming, right? The industry was popping. It was post-Civil War. We were growing from an infant nation into a world power. And in that time, the things that were happening here were pretty phenomenal. So I think that's probably the time period that I'd want to see is that sort of late 19th century.

Rob Lee: Now, this one is like almost a palate cleanser, right? For the thinking that goes into that previous question. Maybe, maybe it is, because I know artists and I'm saying that with a little stank on it. They never answered this like directly. So I added the plural to it. What are your favorite colors? Because I know no one can ever tell me one color is always like, well, you know, depends on how I'm feeling. It's like, just tell me the nine colors you got. What are your favorite colors?

Matthew Hankins: Well, so my favorite color is green. I mean, it's been green since I was knee high to a grasshopper, a green grasshopper. I've always been a fan of green. In my modeling, it's all earth tones all the time, and specifically sort of the rust colors of the oranges, reds, browns, yellows, they work for brick, they work for rusty metal, they work for dirt and grime, they're perfect. But you'll notice in my models that I always throw weeds and bushes and stuff because there's nothing, color theory, color wheel, there's nothing like a big orange, brown, red colored building with a piece of green grass in front of it, it is pop. So yeah, green, the color, the answer is green.

Rob Lee: So this is the last one I got for you. So Baltimore is changing, right? So what's one building that you've maybe done a miniature for that no longer exists that you would want to bring back? It could be a building in general, but if there's one that you've done a miniature for to bring it all together, you know,

Matthew Hankins: Yeah, I mean, that pier, man, if I could talk about going back in time, if I could go back and walk through that pier, it wouldn't work now, right? The fire marshal would have a conniption fit. It's a big, giant wooden building over the water. But I mean, it probably smelled horrendous. It probably was gross and dirty. But there's a photo of that building, the Light Street Pier, that appears on a lot of places. I think it's Library of Congress. But the photo site, Shorpy, has posted it. And it's super detailed. You can zoom way into it. And it's just phenomenal. And so that's probably, again, I don't know if we could bring it back. But I would love to see. I would love to see it. Right. I just I don't think I don't I don't think it would fly in 2023. But but that being said, you know, they're reimagining Harbor Place and that whole space. Yeah. And whether they're they're never going to build a big wooden ferry pier down there. But the idea of Baltimore reconnecting with the water. Baltimore doesn't connect with the water. We're a harbor city and we don't connect with the water. We see it, but we build everything with our back to it. If the harbor could be connected to in some manner, whether it be with architecture or with ferries or with you know, being able to go and buy fresh seafood that literally is coming off the boat in Harbor Place in the center of Baltimore. I mean, it would be nice. Maybe don't build the pier, but at least bring back the connection to the water. That's great.

Rob Lee: So in these final moments here, one, I want to thank you for coming on to the podcast. That's pretty much it. You're off the hot seat. Thank you for coming on to the podcast and spending some time with me. And I want to invite and encourage you to share with the listeners where they can check your workout, your website, social media, anything that you want to share for folks to tap in and check out all of the great work that you're doing.

Matthew Hankins: The floor is yours. Super. Well, my website is PatapscoFallsDivision.net. and I can be found on Facebook at Patapsco Falls Division and on Twitter and Instagram at RestoCarp. So yeah, any of those spots, you can find my work and find photos of it and get with me if you have questions and stuff.

Rob Lee: Yeah. And there you have it, folks. I want to again thank Matthew Hankins for coming on to the podcast. And I'm Rob Lee saying that there's art and culture in and around your neck of the woods. You've just got to look for it.

Creators and Guests